For me, life is blurry.

One day, while waiting on the Light Rail platform, a man came up to me and proceeded to wave his hand in front of my face. Now, I’m no stranger to men trying to get my attention in obnoxious ways, but I knew the main reason why he was doing this—to see if I am “really blind.”

I had my white cane with me, but I had no service dog, and I wasn’t wearing those tell-tale, black sunglasses you often see in movies. I was dressed professionally, with my hair up in a bun and in full makeup. So, naturally, when I pointedly told him that I could, in fact, “see” him, he was quite startled . . . and embarrassed.

Of course, this wasn’t the first or last time someone doubted my disability and felt the need to “test” me. Possibly the most significant thing I’ve learned about disabilities since losing my right-side vision in both eyes (called hemianopsia) due to multiple surgeries to remove brain tumors is that many apparently able-bodied people have lots of preconceived notions about what constitutes a disability and how disabled people are supposed to look or act.

Taking on Ableism…

As a visually impaired person, the most common reactions I receive when I disclose the nature of my visual impairment is, “But you don’t look blind,” or “But you don’t look disabled.” But what does that really mean? It seems that—in order for my disability to be recognized by the able-bodied—I must conform to people’s shallow understanding of disability, or risk being labeled a “faker.”

It’s disappointing to know that in the years since the passage of the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act), not much seems to have been done to educate people on the variety and severity of disabilities. People seem to view disabilities as one, solid, unchanging minority group, rather than a fluid spectrum that knows no gender, sexuality, ethnicity, or age. Moreover, society tends to view disability as something that can only be seen on a physical level, completely discounting the fact that mental illnesses are disabilities, too.

Years ago, a man called Kristen Waldbieser’s use of a wheelchair “a hoax” when she briefly stood up at Disney World. In an Instagram post, she stated, “No, I don’t need my wheelchair every day. But my wheelchair helps me get places that I otherwise probably couldn’t go . . . just because I don’t need it every day doesn’t mean it’s not real and it’s not needed. It’s not a hoax. And even jokingly, it’s not okay to say that to someone.”

Unfortunately, stories like Waldbieser’s are all too common. There needs to be greater focus on disability education and awareness, and disability needs to be seen for what it is: a social justice and human rights issue. Moreover, people with disabilities need to continue sharing their stories and seeking reform, but above all, the public needs to listen and understand.

… with a Sense of Humor

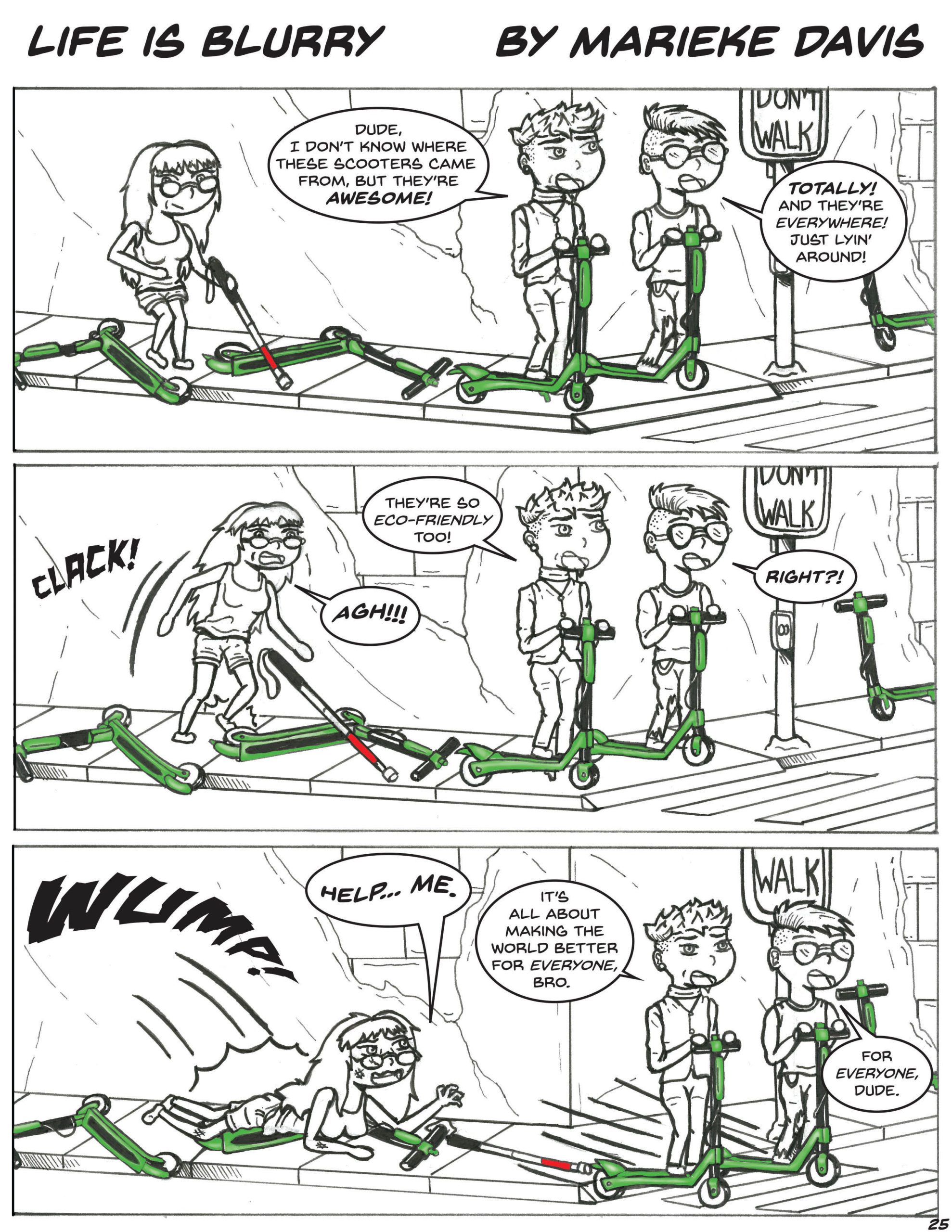

My intention behind my mostly autobiographical comic strip, “Life is Blurry,” is 1) to present the ironies of the world through the perspective of a visually impaired visual artist such as I am, so that the disabled community can laugh along with me, and 2) to educate the able-bodied using the most effective means I know: humor.

Life is Blurry, Comic Strip #25

Arizona native Marieke Davis, a “visually impaired visual artist” since age ten, found a therapeutic passion for narrative art that guided her studies and career. A 2017 summa cum laude ASU graduate, she completed a BFA in Art/Drawing, and minors in English Literature, Women’s & Gender Studies, and Creative Writing.

Believing that art should be inclusive, not exclusive, the first installment of her graphic series, Ember Black (Prologue/Chapter 1), was produced in print and audio, for the visually impaired, winning the 2016 Herberger IDEA Showcase Audience Choice Award. She was also awarded a 2017-18 VSA Emerging Young Artist by the Kennedy Center for excerpts from her online, autobiographical comic, “Life is Blurry.”

She completed Chapter 2 of Ember Black in print/audio, thanks to an Arizona Commission on the Arts grant and is currently the feature comic artist for LivAbility Magazine, published quarterly by Ability 360.

A frequent contributor to the Phoenix Comic-Con/Fan Fusion, she aspires to complete an MFA in Illustration, so that she may share her passion for inclusive visual art with student artists at colleges across the nation.

You can check out more of Marieke’s work on her website and follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.